With a big smile on his face, Richard Visser talks about his scale-up as a child during puberty. “As an adolescent, you sometimes want to do things differently and sometimes you have to do things you don’t like at all.” Six years ago he started his chip company SMART Photonics. He is convinced that these photonic chips will contribute to a better world.

With applications in, among others,

– the telecom sector; sending more data,

– medical care; more accurate and faster measuring and analysing what’s wrong with someone,

– safety; autonomous driving, and in recognising objects in front of and next to the car.

And there is much more, but what, we don’t know yet, according to Visser. “As a company, we need to grow up quickly to ensure that all of this will actually be possible in the future”.

“We are really on the eve of something very big. Something similar happened with electronic chips.” Visser adds Ansoff’s product/market matrix. He is responsible for the development of the electronic chips. “Fifty years ago, electronics were still in their infancy. At one point, this development went very fast, with the advent of microelectronics and electronic chips. Nowadays we think it’s normal that we have a computer on our desk and a smartphone in our hands.”

He mentions the development of the radio. There used to be the tube radios. Then came the transistor and the transistor radio. “At one point it all became so small that someone came up with the idea: now I can also put it in my car. This is how an existing product, the radio, found a whole new market, the automotive. And now there’s a chip in your phone that you can use to receive radio.”

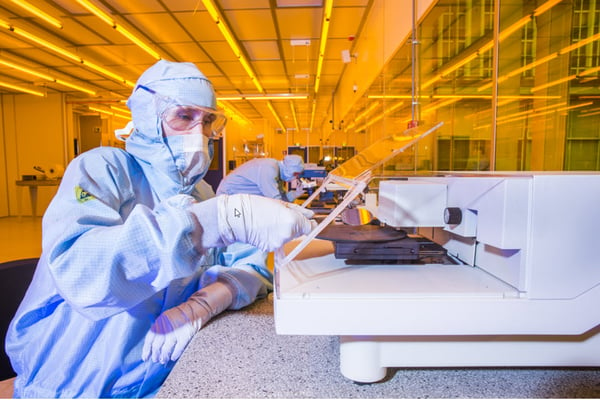

Visser has his background in electronics and the semiconductor industry. He worked for ASML and Philips, among others, and saw the semiconductor industry develop into what it is today. “The development of the semiconductor industry has led to large companies such as ASML, Intel and NXP.” Visser sees a similar future in the development of photonics. With semiconductors that work with Indium phosphide (InP) and not with Silicon. “The most important function in our chips is the generation of light and for that, we need Indium phosphide (InP). Making those chips is a bit like making the electronic chips, but also requires specific experience. We are looking for people with experience from the Silicon world; we train them further ourselves.”

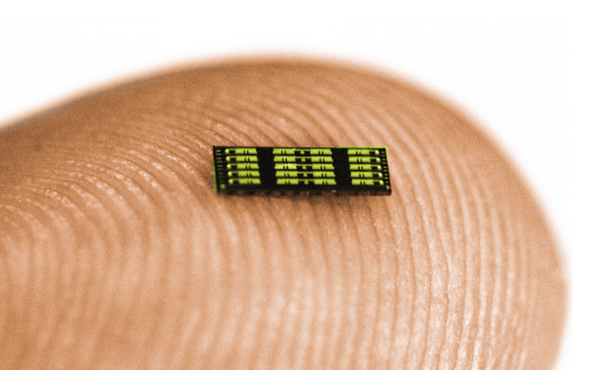

It is a new technology that is mainly based on lasers for telecommunications, explains Visser. “Photonics has been known for forty years. Making complex chips out of it in which many different components are integrated within a few square millimetres is new though. And all the more so because these chips can also be used in other markets such as aviation, healthcare, medical technology or automotive.”

Richard Visser, SMART Photonics

“Until recently it was very difficult to make such a chip in this technology. That was actually only done on a very small scale by highly educated technical people. The Technical University Eindhoven has further developed this technology over the past twenty years, comparable to the technology of electronics. They have made standard building blocks out of it, just like Lego. These building blocks can be combined into a new functionality, a chip. With software, the customer makes a chip design, he gives that design to us and we turn it into a chip that the customer uses in his product.”

Visser brings the photonic chips to the market with SMART Photonics. “Developing technology is one thing but in the end, you have to be able to make and sell it.” With SMART Photonics, including the chip factory, he now works in the same building as he used to work at Philips; High Tech Campus 29. At that time, photonic components, lasers on InP, were also developed in the same building. That department closed in 2011. Visser brought the people from that department back into the technology and now more than fifty experienced people work at SMART Photonics. “They mainly bring along the knowledge of ‘making’. Add to this the twenty years of development of the TU/e, in the new technology, and we have SMART Photonics. This is how we try to conquer the world.”

“Six years ago, for most people, photonics was really abracadabra. Almost no one in the world then made this kind of complex chips. In 2013, SMART Photonics had a world first, a Multi Project wafer with fifteen different chips for fifteen different customers. The chips are made on such a wafer, a round disc of 7.5 centimetres in diameter. “That’s when we first introduced this new technology to the market”

“We were as happy as a child. Chips emerged that exceeded all our expectations. As a manufacturer of these chips, Visser wants to become big, but he also sees the value for the Netherlands Inc. “We thought: This has enormous potential, not only for us as a chip maker, but especially for companies that can make better or even new applications with the chips. But we can’t do that alone. Ultimately, from that thought, PhotonDelta came into being.

“At the time I literally said: ‘SMART is this little tree and this is the landscape. If we want to grow as a small tree, we have to develop the landscape as well’. Together with Robert Feelders, who then worked at TU/e and is now CFO for SMART Photonics, we brought together about twenty people: users, professors, people from governments such as municipalities and provinces. They too saw the possibilities and that’s where PhotonDelta came into being. All parties then put some money together to ask consultancy company Berenschot to write their first market report. “Now, almost five years later, an enormous amount of work has been done by the PhotonDelta people, especially Ton Backx and Ewit Roos. You see that photonics is also embraced by governments.” Visser was there on 15 July when the National Photonics Agenda was presented by René Penning de Vries, the first man of Photonic Netherlands, to the State Secretary for Economic Affairs and Climate, Mona Keijzer.

Raising money is still a big challenge. “High Tech companies are always struggling to raise money. And especially when it comes to developing a technology that is not yet understood by everyone. Our challenges are extremely big. We need to enthuse people, convince them that something really special is happening here and that we need money to develop it. Yes, it’s been difficult, but we have so far been very successful in raising funds to finance our growth. The customers are particularly important in this respect. Fortunately, we are not lacking in interest from the market. Large companies are paying attention to what we do and especially what we can do.”

Spending money is even more difficult, Visser admits. Every euro is turned around at least five times before it is spent. “I remember very well that I was going to buy our first machine. They asked 300,000 euros for that. Blisters on my tongue it cost me, but ultimately I got it for 240,000 euros. But then I finally had to pay it. I sat in front of the button for half an hour and checked again and again whether I had filled in everything correctly.”

Visser compares the starting phase with that of a baby or toddler. Everything is fun and new, with lots of learning, trial and error. Then comes puberty, SMART Photonics is now in the middle of that. “Adult decisions have to be made, but in fact, you haven’t reached that point yet. Now we’re working hard to stabilize the processes, to make those chips, and ultimately to be able to produce large volumes. More and more new people are also coming to work in the company with positions such as communication advisor, quality and safety manager, who have to ensure that the organisation will also grow up.”

In a fast-growing company, enough things also go wrong. “At the end of last year, for example, several machines broke down, it seemed as if everything went wrong at once.” Visser calls that period “a perfect storm”. “But you have to go through it to grow up. Because that’s what Visser wants: to quickly become a mature company that can supply the best chips in the world to the largest companies in the world in large volumes. To do this, he has to invest at the right time so that the factory that enables mass production can be built.

“We get a lot of help from the neighbouring companies like ASML. Also from the TU/e and the municipality of Eindhoven, the province of Noord-Brabant, the Dutch government and Europe. The technology is promising and can, therefore, make a major contribution to employment and the economy. Bert Pauli, Commissioner for the Economy of Brabant, is very involved and sees the possibilities for the province.”

Visser is confident that the technology and the company will be successful and that this will happen very quickly. “In ten years time, you will be in your autonomous car, reading some e-mails or watching a movie. Then you think back to this conversation and say to yourself: Visser was right. They succeeded.”

Photo (c) Jonathan Marks

Article (c) Innovation Origins