This blog comprises a collection of articles on innovation written by Hubert Martens, the CEO and founder of Salvia BioElectronics. Originally shared on LinkedIn, Martens intended to spark a conversation about innovation and introduce the innovation model he and his team developed over their careers.

Mastering the Art of Innovation: A Guide to Building Truly Valuable Solutions for a Better Future

"I wish we talked more about innovation. Not in terms of cutting-edge new technological development – there’s arguably enough gibberish about that out there – but of true innovation: how brilliant ideas arise and how to consistently create more. Like many of the people I connect with here, innovation has been my bread and butter for the last decade. I’m a med-tech guy: my mission is to fix problems affecting people's health and lives. Together with brilliant teams, I have founded and developed three successful med-tech start-ups where innovation sat at the very core of the business. I believe there is a model for innovation and I want to share it with you.

In 2014, we successfully exited Sapiens Steering Brain Stimulation to Medtronic. Sapiens developed the world's first directional brain stimulation solution and jointly we launched our product SureTune to the market. In 2017, I co-founded Sirius Medical, a surgical technology company that provides breakthrough localization technology enabling surgeons to remove tumors in soft tissue. It’s currently in commercial stage in the EU and USA. Salvia BioElectronics, the most recent enterprise, aims to help people who suffer from severe migraines. For all three companies, my team and I successfully raised funds, built a team, and developed innovative medical devices that provide solutions to pressing unmet medical needs.

Hardly any of it would have happened if we had thought of innovation in the conventional, stereotypical way. We don’t talk enough about how breakthrough innovations come into the world, and the result is that most people think of innovation as a serendipitous event. People tend to think there’s no way to come up with innovative ideas at will – they come to you through abstract forces like inspiration, chance revelations or sheer stroke of luck.

It's true that there is no formula to create breakthrough solutions. But my experience showed me there can be a structured, disciplined approach to innovation. It doesn’t need to be talked about in the language of gurus and magic formulas. It is a process we can follow to dispel many of the struggles we go through in the innovation process.

I want to start a conversation around innovation. Firstly, because when I was younger and less experienced, it would have helped a lot if someone told me these things. So: I hope this helps.

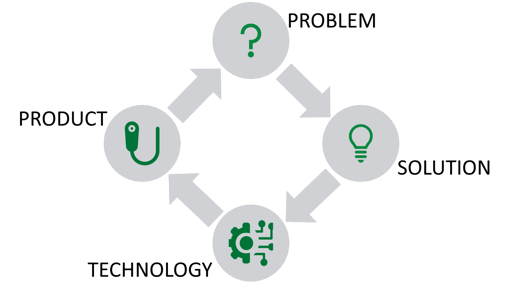

My team and I have created a process that informs and guides our efforts to bring solutions into the world. The gist of it is that we think of innovation as a continuous cycle of four steps.

I mentioned the process is circular, so after the Product phase comes: repeat.

Developing an innovative concept that will one day become a product isn’t simple, and so, since we’re all human, it’s unlikely we get it right quickly. So, after developing your first concept, you go back to the problem stage and start over, going through the stages again to develop a new, more advanced concept. And then again, until you inch closer to having a prototype for testing. Even then, any prototype or product will be ready for improvement almost as soon as it’s finished, so you’ll be able to go back to the start right away.

It’s imperative to go through the cycle multiple times, and each time will get you closer to the perfect product. But especially early on, products will inevitably leave something to be desired. That’s what early products are – and should be – like. So, whenever you bring one into the world, it will most likely leave something to be desired. This is perfectly fine: you’ve learned a great deal and you’ll apply this knowledge when you start over from the problem stage, and the cycle begins anew.

Similarly, the cycle also begins anew each time you find yourself stuck at any stage of the cycle. If, for example, you’re struggling to get past the technology phase, where you look for technology that can help you realize your concept solution, it might be useful to step back and look at the problem again.

One of my favorite quotes about the innovation process is: “No wind favors him who has no destined port.” The guy that came up with it was hardly a tech specialist – the 17th century anthropologist Michel de Montaigne, who became famous for his skeptical, rationalist way of making sense of the world – but the quote does encapsulate a key problem plaguing countless innovation projects and companies, and a concept my team and I often go back to. Namely: If you don’t know where you’re trying to go, you won’t get anywhere. Or, to translate it into a context closer to us: If you don’t know what problem you want to solve, your creative efforts are unlikely to bear fruits.

Problems are the key to finding solutions, even if so many people don’t think that way. Many start thinking of products long before they’ve thought about what problem they’re trying to solve. “We have this shiny new technology, what can we do with it?” you can almost hear them say. But this approach is unlikely to be anyone’s road to success, even if they had all the talent and resources in the world. Take, for example, the Google Glasses that entered the market in 2013 and cost about $1,500 apiece. They were “smart glasses” with a built-in camera, voice controls and a revolutionary screen. But it was hard to understand what problem they solved. They seemed like an expensive geeky gadget that tech enthusiasts would love. But outside that bubble, why would people buy them?

I would go as far as to say there can be no innovation without a well-defined problem. To produce any innovative solution at all, you have to address a problem people are struggling with, and the current solution to which is weak. Google Glasses didn’t solve any problem. By 2015, they’d been retired from all markets.

The key to solving any problem is to know it intimately. That’s why the Problem stage is the most important part of the innovation cycle, and no amount of time spent here is too long. What is the problem you want to solve? How are people affected? What solutions already exist out there? In what way are they not good enough, and the other way around: what aspects are good and you’d want to retain?

At this stage, my team and I like to read everything we can about the topic, talk to experts – and listen to them! Usually, there are multiple stakeholders involved, and that is particularly true in health care: patients, physicians, nurses, insurance companies… Each might have a different take, and we want to make sure we understand all positions.

All this information helps us define the problem better. And a deeper understanding of the problem invariably provides the wind boost in our sails and leads us to a better solution.

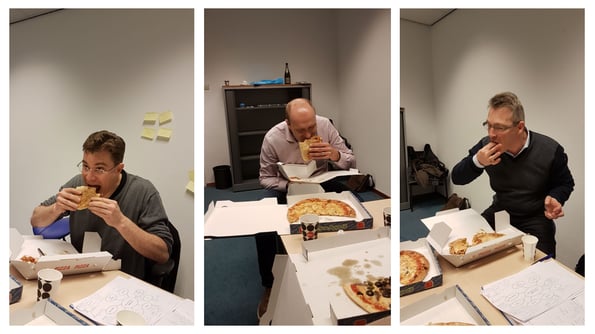

We innovators can prove one cliche about our work true: Devising an innovative concept does come with lots of pizza and endless scribbling on whiteboards. After you’ve thought long and hard about the problem you’re trying to solve (for more on this, see my previous post) and know it inside out, it’s time to get the creative juices flowing. It’s what my team and I call the “Solution” phase of the innovation cycle: you put smart people together in a room and think about how to address the pain points of the problem you are trying to solve.

It’s time for blue-sky thinking. When we’re here, my team and I want to be able to think freely, so we get rid of all possible constraints that can impede our creativity. For example, don’t get caught up with technological details, time or resource constraints. Don’t worry about going off-piste, either! We usually allow ourselves to have fun and be taken into surprising new directions at this stage, following new leads, ideas, and concepts. To people with curious, inquisitive and creative minds, this is the playground stage.

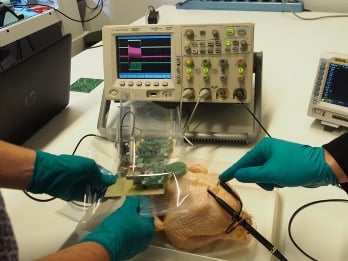

Of course, how exactly you invent a solution is different each time you try. In many cases, we already have an inkling when we define our problem for the first time. At my company, Salvia BioElectronics, for example, we set out to help patients suffering from severe migraine. Migraine is both very prevalent and highly debilitating, and drugs have little or no effect on many patients. As soon as we delved into the problem, we knew our solution would be a device that could stimulate nerves and trigger the natural mechanisms of the body that relieve headaches.

Of course, how exactly you invent a solution is different each time you try. In many cases, we already have an inkling when we define our problem for the first time. At my company, Salvia BioElectronics, for example, we set out to help patients suffering from severe migraine. Migraine is both very prevalent and highly debilitating, and drugs have little or no effect on many patients. As soon as we delved into the problem, we knew our solution would be a device that could stimulate nerves and trigger the natural mechanisms of the body that relieve headaches.

The best thing you can do with that inkling is to try and get feedback from people in the field where the problem lies. What do they think about your idea? Have they seen something similar? What worked, and what didn’t? And – most importantly – why..? They can give you guardrails that let you know how your solution could work – and make you learn more about how your ideas really address the problem at hand, and what gaps may still remain.

In our case, we talked to physicians, headache specialists and to a lesser extent to patients, to understand what a solution could look like. Many of the early solutions we came up with turned out to be impractical: some were obtrusive, others proved to be too invasive or too complex for available modern-day technology. That’s not a problem, we kept thinking without putting pressure on ourselves – remember, no constraints!

Once your concept solution starts shaping up, it is of paramount importance that you translate it into tangible benefits (value) for the key stakeholders involved such as patients, physicians, and payers. This allows you to rank and compare concepts and, importantly, provides direction to the creative process to ensure you converge on a “true” solution that tackles all aspects of the problem.

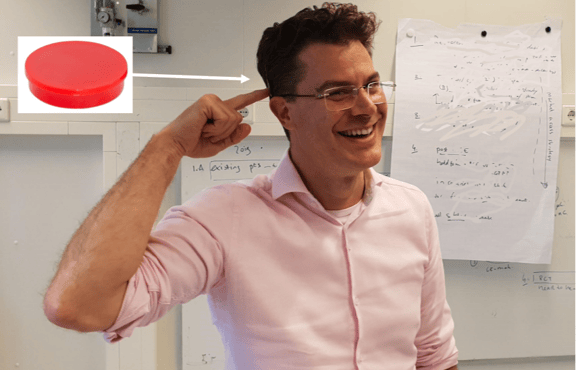

It was during a long creative session that I stood in front of the whiteboard holding a magnet. Looking at it, I realized that it conceptualized the solution we were looking for: it was small, magnetic, and could be easily attached and removed. I showed it by holding it against my temple, and here was our eureka moment: We could create a tiny implantable device with an external rechargeable battery – like the magnet, something that would be invisible during use and that could be removed, recharged and stored away. That wouldn’t have happened had we put too much constraints on the solutions we were trying to find or if we had not remained open to listening to our intuition. We needed to balance creative thinking with staying sufficiently grounded to avoid impossible science-fiction. One crucial aspect: we consistently translated the conceptual solution into something that has tangible benefits for the stakeholders to pick a winner. The whiteboard cliche was proven right once again – but with a lateral thinking twist: who knew whiteboards could turn out useful in more ways than conventional scribbling!

I like to bear in mind that tech shouldn’t be leading our thinking: it should be an enabler. So, it’s imperative that we don’t get distracted by the latest cutting-edge tech: we keep our eyes on the problem and look for what we need. You’ll be surprised how many of the most successful technological innovations came not from expensive and breakthrough new tech, but from innovative ideas that worked to serve a group of people.

Take Apple’s iPod, for example. It didn’t come from revolutionary technology: several portable MP3 players were already available when it entered the market. But what the iPod had that the others didn’t was a very good definition of the problem: Apple knew users needed a tiny, easy to use device to play their entire music library. Most competitors used the shiny new tech – the ability to play MP3 songs of choice at any given moment – but each had a flaw. Some were clunky to connect to laptops and desktops, others too large to fit into pockets, others had low storage capacity or short battery life. The iPod focused on the problem and the users more than the others, then went out to find the tech to make it work, even if it wasn’t the shiny new tech we all dream of inventing when we begin working in tech. The result: the iPod dominated the market as long as it existed.

Many leading tech products resemble the iPod in this way. From the technological point of view, tech enthusiasts might even find them a bit boring. But that’s not the point. What matters is that the product uses technology to solve an important problem for its intended users – and solve it once and for all. Remember the iPod: Even though the tech might not have been top-notch, the application certainly was.

The last stage of the innovation cycle my team and I use to devise breakthrough solutions is the “Product” phase. This is where you bring together everything you’ve learned, studied and tested in the previous three phases to create the first iteration of your solution. Here, it’s all about turning a technologically effective solution into a viable, safe and limited product that will one day, after going through the cycle multiple times, be produced cost-effectively and effectively marketed.

Mind you: emphasis on “limited.” One of the most valuable lessons I’ve learned working to create innovative solutions to med-tech problems in the last 10 years is that it can be counter-productive to aim for perfection immediately. It’s foolish to think any first product concept can be perfect. My team and I know we won’t get everything we dreamed of right away: some aspects of our first concepts won’t check all the boxes. That’s what first concepts do!

But that’s the beauty of it, too: if you try to build a perfect product at the first iteration, you’ll likely never launch. The limitations of having to come up with a prototype force us to focus. We have to pick only a few aspects where we want your product to stand out, and leave the other ones behind for now. It’s time to make tough choices! If we can, we down-select until we have only one key aspect that truly delivers value to our stakeholders. And we put all hands on deck to focus on that one. That way, one subset of users will be very happy. And that’s all you need.

This is important because as I’ve mentioned elsewhere, the innovation process is a cycle. This means that, if you follow this approach, you’ll go through the four stages I’ve described in this series of posts multiple times before you end up with a marketable product. So, it’s key to get a first iteration together. After that, our next job will be to improve it and make a better version. But it’s important to pass through the “Product” phase every time, because each time it gives us a reality check to understand if it solves the problem.

A fantastic example of a company that iterated early and frequently is Tesla. Once they had an innovative concept, a battery-powered electric car, they created a first product that still had a few weaknesses – above all, price. The Roadster, the world’s first legal serially produced all-electric car using lithium batteries, was expensive and elitist: Tesla only sold about 2,450 Roadsters in five years! See how Tesla down-selected here: the Roadster was an amazing car for a niche market, but to get it to the market they sacrificed aspects like its cost, size and comfort. But the company didn’t let this slow it down. They iterated, then went back to the innovation cycle to develop another car that built on the Roadster and could be more competitive pricewise, reaching a wider market. And a few years later came the Model 3, which was more affordable to produce. Tesla did this many times: they built multiple models, launched them, then went back to work, and with each iteration they inched closer and closer to an electric car available for the mass market. I don’t need to tell you where they are now.

So, when you’re developing your first product, embrace that the first generation will not be perfect – it never is. My team and I often remind ourselves that we should not fear imperfection but let it be our friend.

Sapiens, Sirius, and most recently, Salvia. I look forward to hearing how it works for you.

Obviously, it's a model – Being a physicist by training, I like devising models as they help to structure my thinking, but a model always remains a simplification. For me, it’s been so effective that I apply it to every innovation decision-making process I find myself in, and it has become ingrained in my mentality.

As usual, the key turns out to be to focus on our main problem – the very reason we resort to the innovation cycle in the first place: creating innovations that improve people’s lives."