As co-founders of SUE & The Alchemists, a company for applied behavioural science, Klaas Dijkhoff and Tom De Bruyne explore how understanding human decision-making is a key to successful innovation.

Normally, the AI Innovation Center at the High Tech Campus Eindhoven is the place for deep technological research and talks about the power of data science and artificial intelligence. Not this day. Klaas Dijkhoff and Tom de Bruyne, the co-founders of SUE & The Alchemists, a company for applied behavioral science, gave a two-hour talk on how understanding human decision-making is a key to successful innovation. “Every successful innovation has figured out how to tap into deeper psychological needs, problems, desires, fears, and beliefs. Discovering those psychological insights and addressing them in your product is what differentiates products that catch on from products that don’t.”

Klaas Dijkhoff is a former minister, secretary of state, head of the ruling Liberal Party VVD, and twice elected ‘politician of the year’. Tom De Bruyne is a behavioral scientist, entrepreneur, and elected fellow at KU Leuven. With their new company, they try to understand ‘the superpower of behavioral science’. “Understanding human decision-making is a key to successful innovation. The importance of the role of psychology is growing. But how to influence minds and shape behavior?”

Psychological innovation

Building a new technology is one thing, but understanding how we think, feel and behave is something else. That’s why Dijkhoff and De Bruyne are convinced that psychological innovation is way more important than technological innovation, something that will even be more impactful in the coming years, according to De Bruyne. “The future of innovation is psychological, not technological. That’s the key to creating better products.” But a lot can go wrong in that respect, he adds. “You can choose for the manipulation of certain human desires like Red Bull and Donald Trump do, but you can also choose to help people get more healthy, productive, or wise.”

Klaas Dijkhoff

Klaas Dijkhoff

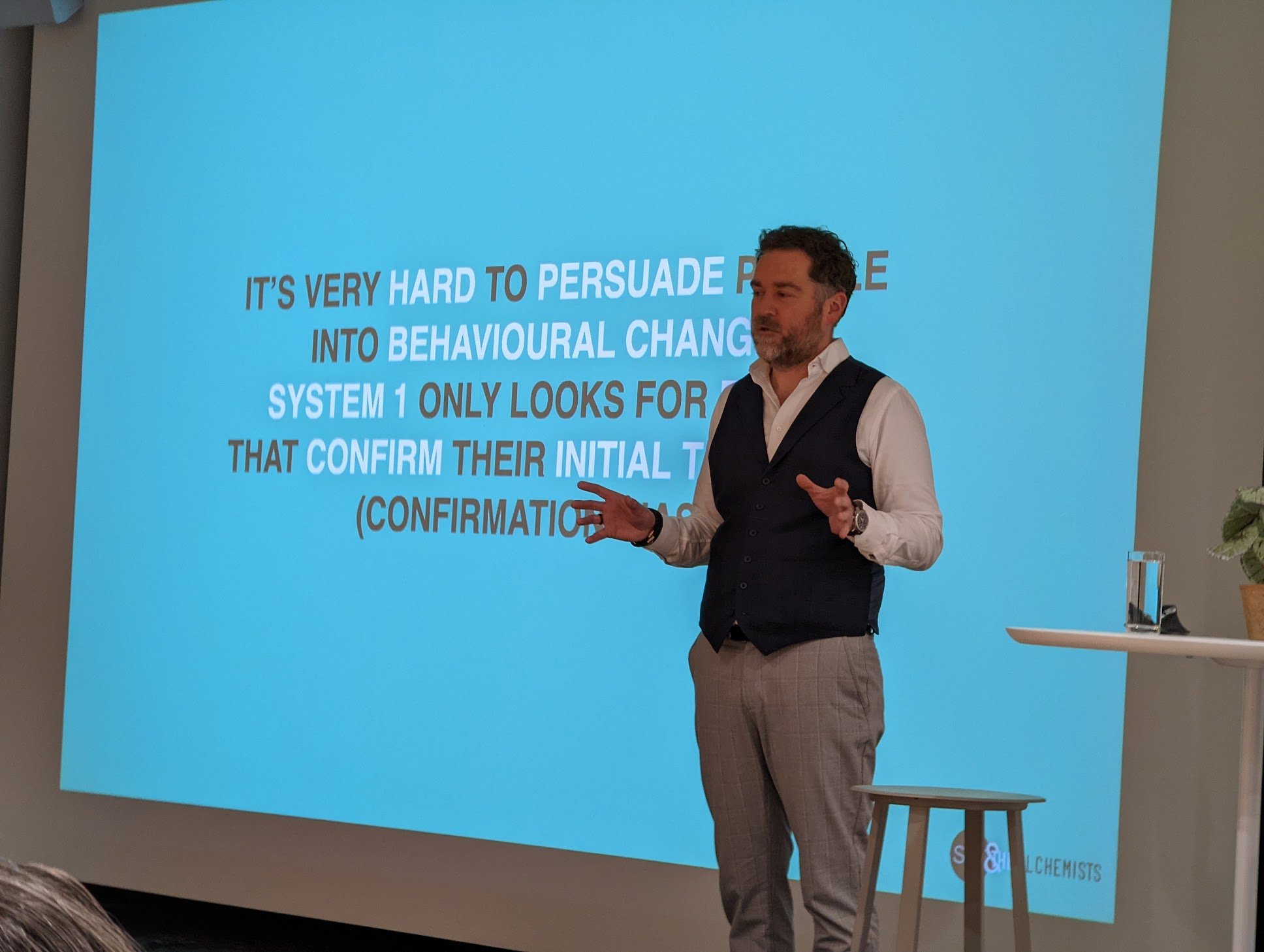

Dijkhoff explains that human beings are functioning on two systems. “System 1 controls our instinct and intuition, it defines our rapid decisions, which account for around 98% of all our actions. This system sends messages and suggestions to system 2, which works slower, turns these suggestions into convictions, and acts more rationally than system 1.” Our instincts prevent most of us from behavioral change, which is totally due to system 1, because it keeps looking for confirmation of our initial thoughts. “The confirmation bias: even if you know if something is not true – if it fits with your beliefs, you will want to believe it. You’ll just disregard the facts. That’s why you want to drink Red Bull. You know it’s disgusting but that knowledge is not going to persuade system 1.”

There are lots of opportunities for psychological innovation in practice, De Bruyne says. “To get there, we want to offer shortcuts to system 1, and post-rationalize these. That’s our basic framework.”

Thinking about the shortcuts

The presentation is filled with examples that show how behavioral science works in everyday life. We learn why Ikea places the restaurant at the beginning of the store (“The food there is so cheap that you immediately think the rest of the shop can also be bought at a bargain”) and why Louis Vuitton stores first show you the most expensive stuff (“it makes you want to buy their cheaper products”). It’s all about choice architecture, “thinking about the shortcuts, anchoring people.”

Thinking outside-in and putting the user first make you aware of the job-to-be-done, Dijkhoff adds. “Pitch the product or service as the best way to help people to reach their goals or to fix their problems. Even if system 2 has no idea what this solution is really going to bring you, system 1 is already convinced. What we often see are solutions looking for a problem. Remember how Steve Jobs succeeded in this? You didn’t know why you needed that new Apple product, but you wanted it anyway.”

A theoretical sidestep follows, about undesired behavior that is provoked by comforts and anxieties on the one hand, and desired behavior connected to pains and gains on the other hand. After citing Clayton Christensen with his famous milkshake-job-to-be done, other examples of behavioral design are presented. We learn how companies like Spotify, Airbnb, and Uber all found out where to put these shortcuts to system 1.

Another important part is how to frame the choice, Dijkhoff says: “When I ask my wife what we could be doing on the weekend, I normally give her a couple of choices. I know that if give her just one suggestion, we will endlessly discuss if this would be good or bad. But if I present three choices, I unconsciously make sure all three are things I would like to do. And we always find something nice.” On another level, Dijkhoff shows how the Brexiteers were able to “take back control” by offering a choice between mass immigration and money for the NHS. “Now, that’s some choice framing. And very effective, because the Remainers had to start using rational arguments to explain why this is a strange way of putting it, but in doing so, they were adding to the power of the Brexit arguments. It’s exactly the same with Donald Trump: he presented himself as a dealmaker who would make the Mexicans pay for that wall. His opposition took him literally, his fans didn’t. He forced the opposition to talk about this problem they really didn’t want to talk about.” What they could have done instead? “Don’t get lured into the opponent’s frame. Don’t react, or at least don’t put facts against feelings.”

Vegetarian

So what does it all come down to? De Bruyne: “Designing an intervention to make the undesired behavior impossible will help people overcome their incapability to change. Motivate them by making desired behavior easy and triggering their behavior. That’s how I became a vegetarian.”

Klaas Dijkhoff and Tom de Bruyne in the AI Innovation Center

Klaas Dijkhoff and Tom de Bruyne in the AI Innovation Center